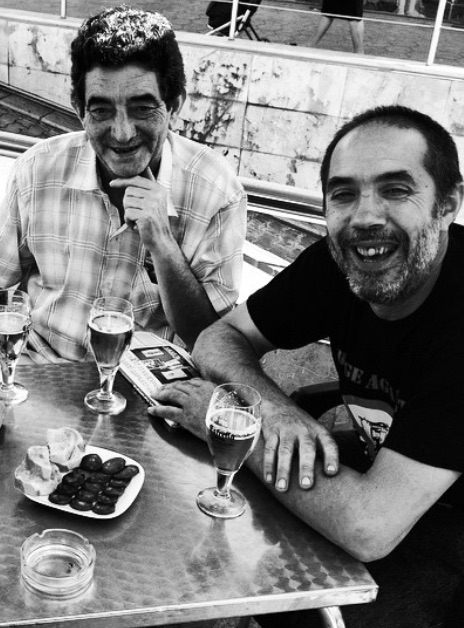

Everyone seems to have a story about Laureano Serres and the stories tend to converge in a few places: his frenetic energy, his deep loyalty to friends and family, his extreme generosity, and his gargantuan appetite for wine. But Laureano’s affable manners conceal a profound influence on the natural wine movement, making his revolutionary ideas seem ordinary, even provincial. In the late 1990s, as winemakers all over Catalonia scrambled to obtain flattering reviews from critics who favored a generic international style, Laureano turned decidedly in the other direction, opening the path for a new generation of Catalan natural winemakers.

A former computer programmer, Laureano returned in 1996 from Madrid to his home town of Pinell de Brai in the Terra Alta region Southwest of Tarragona province. The following year, he became president of the grandiose Catedral del Vi, a functioning wine cooperative, designed by students of Gaudi prior to the Spanish civil war as a monument to working class solidarity. Sympathetic as he was to the cooperative’s commitment to producing affordable wine for real people, he quickly lost interest in a model of production that prioritized quantity over craft. In 1999, he set up shop directly across the street from the Catedral, vinifying 500 liters of a traditional Catalan field blend from his grandfather’s vines at Finca Caibelles and baptizing the new domaine as Mendall. During these first few years, Laureano replanted fallow parts of the vineyard with Bordeaux varieties, seen at the time as the prerequisite for “wines of quality,” an irony that in retrospect strikes him as dark comedy. Since 2017, Laureano’s viticulture is centered in the neighboring village of Vilalba dels Arcs, at the lieu-dit of Terme de Guiu, a limestone amphitheater planted to massale selections of white, red and grey Garnatxa, old Carignan, and Macabeo, along with a few errant vines of Malvasia de Sitges. Perched at 400 meters above the Mediterranean, Terme de Guiu is exposed to famous garbinada winds of the Terres del Ebre.

From the beginning, Laureano was committed to working with organic grapes and wild fermentation, but it was only after 2003, when he “forgot” to use SO2, that the real period of experimentation began. In those early days he made friends with the late Marcel Lapierre, who introduced him to the world of natural winemakers in France. It didn’t take long for Laureano to learn the ropes. By the late 2000s, he was experimenting with everything from carbonic maceration to fermentation in amphora, a necessary period of trial and error for what would come next. These days, Laureano has settled into a unique methodology of cellar work that might be described as orgnized anarachy. Though certain parcels are always vinified in the “traditional” manner – pressed whites, macerated reds, bottled dry – every harvest brings surprises. On a surface of about five hectares, Laureano might make up to 16 cuvees: macerated whites, red/white co-ferments, barely sparkling frizzantes, and oxidative garnatxas. Anything is possible and most decisions are made spontaneously, based on the conditions of the harvest.

Many years ago, Laureano often packed his van full of eager young vignerons and drove up to Barcelona with unfinished samples. Most tasters dismissed them as heretics but a few had the good sense to see what is now obvious. These young utopians were on a mission to restore what those who built the grand cooperatives of the 1930s had lost: a basis for real solidarity among artisan farmers. On the surface, it may seem like a raucous party – and it is! – but Laureano’s contribution to Catalan wine is nothing short of revolutionary.